Intro

I recently participated in my very first data science competition. Being less than a year into learning Data Science, this is my first competition. I’ll put the cart before the horse a bit. Surprisingly, I did better than I thought I would. But since this project is associated with one of my official projects in my Data Science curriculum, I had to stop at some point… at least as far as my curriculum-project is concerned. I will continue to refine my methods and models as time permits; there are 9 months left in the competition. As I write this, I currently sit ranked 873 out of 9742 competitors… the 91st percentile.

The competitor in the top spot on the leaderboard built a model with an accuracy of 82.94%. My best model features a leaderboard accuracy of 81.82%. That doesn’t seem like that much of a difference, does it? But, as I would come to learn, in Competitive Data Science, that is a rather large rift. For example, for the top 50 on the leaderboard, the difference between the rank 1 competitor and the rank 50 competitor is 82.94% vs. 82.68% accuracy, respectively.

But this article is not about how “good” (or “bad”) I may be doing in the competition. I wanted to write this post to document my experience from the the Competitive-Data-Science-Beginner’s perspective: I have learned quite a bit along the way while participating in this competition. The goal and point of this post is to document all of the challenges a budding Data Scientist may encounter as someone new to these competitions.

Before I get into that, I ought to provide some details about the competition itself for context. It is the Pump it Up: Data Mining the Water Table, hosted by DRIVENDATA. I will provide my own quick summary of the competition but the official problem description for this competition can be found here.

Competition High-level Summary

This is a multi-class classification machine learning competition. We are given data from Taarifa and the Tanzanian Ministry of Water. Using that data, our goal is to “predict” (classify) which pumps are “functional, which need some repairs, and which don’t work at all”.

Getting Started

Of course, every seasoned and even budding Data Scientist approaches each problem with structure and some idea of a workflow. One common workflow most of us are familiar with is the OSEMN workflow. I won’t bother diving into the details explaining that particular workflow since this post is written for Data Scientists or those interested in the field. But it follows the pattern we are all familiar with:

- Analyze and get to know your data

- Transform data as necessary (given insight from above analysis)

- Build models and make predictions

- Iterate as necessary

The Devil is in the Details

If only it were that easy, everyone would be doing Data Science and/or competing for the cash typically awarded in these competitions. In Machine Learning, we learn about various algorithms geared for classification; for examples, DecisionTreeClassifier, RandomForestClassifier, XGBClassifier etc.

Some algorithms are more flexible than others by default. For example, the XGBoost library’s XGBClassifier can handle null/missing values; whereas the DecisionTreeClassifier and the RandomForestClassifier cannot.

Null/Missing Values Were Pivotal

As it turns out, null/missing values played an important role in this project. At least part of this idea is nothing new. Budding Data Scientists learn that null/missing values usually have to be dealt with and are dealt with differently depending on the data type of the feature containing null/missing values. For example, for a categorical string variable, we might impute the string “none” for null/missing values; for a numeric continuous feature, we usually impute some aggregate value such as the mean, median, or mode. In some cases - in particular in the continuous-feature case - null/missing values may actually be meaningful; so imputing any value at all to replace null/missing value might actually be an error that could lower the accuracy of one’s model.

Outliers and Non-Normal Distributions

We also learn to identify outliers and analyze whether we should impute appropriate replacement values. But in some cases, the prevalence of values that are not outliers could occur in abundance to throw off a would-be nice normal distribution otherwise.

For example, a continuous feature that has a distribution of values where one (or only a few) literal-value dominates the distribution. In this project, roughly 98% of the num_private feature-values are the literal-value 0. We learn that a feature that has only a single constant value will not contribute any importance in classification. In this case, it seems intuitive that num_private should probably be dropped since 98% of all observations have value 0 for this feature. But, there is that possibility that this conclusion turns out to be “incorrect” in the modeling phase, resulting in a lower accuracy if this feature is dropped.

High-Cardinality Categoricals: the Nemesis of One-Hot Encoding

To present another complication, there is the matter of categorical features. In this particular project, there are (string-type) categorical features with unusually high cardinality - i.e. the magnitude of the set of unique values. For low-cardinality (for example, for maybe up to about 20 or so unique values), we learn to One-Hot Encode and transform the set of unique values into new binary (values are 0 or 1) columns for each unique value. If we have more than a few categorical features that are One-Hot Encoded, this can present the problem of intractability introduced by the “curse of dimensionality”… because we end up adding more and more columns to our dataset.

In the data set provided for this project, there are three such high-cardinality categorical features, each containing about 2000 unique values. IF one retains each of those AND One-Hot Encodes them - remember, machine learning algorithms expect numeric data, so string-categoricals must be encoded - then at least 6000+ COLUMNS will be added to the data set. Suppose we keep the original 27 (30 minus the three One-Hot Encoded features); then, since we are given about 60,000 observations, we go from \(60000 \cdot 30 = 1800000\) cells to \(60000 \cdot (27 + 6000) = 361620000\) cells! Now let’s assume that each cell, ON AVERAGE, contains 4 bytes of data (4 bytes if numeric, your typical int, OR 4 bytes of string data, 4 characters… which is conservative, at best). In the first case (all rows, not One-Hot Encoded), that amounts to about 7.2 MB. In the latter case, we jump up to 1.44648 GB (Gigabytes)!!

Admission

I actually tried this approach during my first few days while working on this project. I stubbornly let it run through to completion. Note that I am leaving out some detail, here. When I say “I let it run”, this means that I did some basic EDA (Exploratory Data Analysis), some preprocessing to transform data as appropriate (e.g. replacing null/missing values), and then built some basic models. I started with the RandomForestClassifier algorithm. Letting this process run through to completion required more than 48 hours.

Interlude: Cloud Compute to Facilitate Parallelism

At this point, I thought I needed one of two things (or possibly both):

- more computing power by virtue of clustering (in the cloud)

- “better” feature engineering (starting with an alternative to One-Hot Encoding)

The root of this particular subproblem is: the curse of dimensionality must be dealt with.

At the time, I thought that if I invested some time upfront to build a Cloud Compute infrastructure, I might be able to leverage the Dask framework in a Kubernetes cluster… with the point being to offload GridSearchCV and model-building to this infrastructure while I concurrently worked on refining the next iteration of analysis/preprocessing/model-building. I envisioned the “perfect lab” for this project and that, by using it, the 48+ hours process above would occur in mere minutes. I would be able to try 10,000 by 10,000 parameter grid searches with ease and they would happen in seconds, right? RIGHT?!

WRONG! Boy was I naive! I thought I could short-circuit my path to success merely by throwing a bunch of computing power at the problem and simply “trying” a large space of empirical possibilities.

While this could definitely facilitate a project, it requires a lot of work to set up the infrastructure. I did complete this in the end. I got the infrastructure working and my notebooks would use the remote Dask scheduler and workers in the Kubernetes cluster. But this was just Step 0!

The problem was that not only did I need to refactor my code to incorporate the Dask API to do parallel-processing with the cadre of Dask workers I now had running, but I had to refactor my code to parallelize the data across the cluster as well as the processing.

In the end, this would amount to a complete rewrite of my project from ground-0. This may be something I return to in the future. But I just didn’t have time for this now.

So that left me with perhaps the better option to begin with: “better” feature engineering (starting with an alternative to One-Hot Encoding).

Note: This may be my first official “no duh” moment in this post since most of you are probably thinking exactly that.

Target-Encoding: the Nemesis (of the Nemesis of One-Hot Encoding) of High-cardinality Categoricals

This post is not intended to fully develop the idea or justification of Target-Encoding. But what I will say is that, when used correctly (see the reference), Target-Encoding can completely eradicate the curse of dimensionality brought on by One-Hot Encoding a High-cardinality categorical feature. Stated more explicitly, Target-Encoding uniquely transforms string-categorical values into numeric encodings and retains some relationship to the target - this is NOT the same thing as Label-Encoding. Again, see the reference for a complete understanding, which is vital. I have listed a paper in my references below which provides a detailed study of dealing with high-cardinality categoricals.

Additionally, when a categorical is not necessarily of high-cardinality but is, perhaps, low-to-moderate cardinality - i.e. when One-Hot Encoding will not result in intractibility - it has been shown that TargetEncoding can result in a more performant (read: higher accuracy) classification model relative to one produced in which One-Hot Encoding was used! But the delineation of when to use One-Hot Encoding vs. Target-Encoding for low-to-moderate cardinality categorical features is often not clear and probably ought to be tested empirically.

Other “Manual” PCA and Techniques used to Address the Curse of Dimensionality brought on by High-cardinality Categoricals

Target-Encoding seemed quite miraculous. But, during my EDA, I noticed that each of the high-cardinality categoricals had a few things in common (aside from the obvious: being high-cardinality):

- they are

stringdatatype - each had a lot of what appeared to be duplicated information only in representation - for instance, there could be many so-called “unique” values that differ maybe only by upper/lower-case, whitespace, or Levenshtein Edit Distance

The point?

Prior to Target-Encoding, it might be a good idea to “normalize” the set of “unique” values of each high-cardinality string-categorical feature so that these “duplicates” are smashed down into one unique representation.

Text-Analysis (NLP) Techniques Brought into the Mix

Many of you are likely very familiar with this already. In my case, I used KMeans classification on top of TFIDFVectorizer, initialized with a set of preprocessing rules - for example, to impute lower-case, convert all whitespace to a single “_”, and remove all non-alphanumeric characters - as an experimental technique to reduce dimensionality by almost one full order; that is, 2000+ unique categories classified down to less than 200 unique class representations.

Modeling results showed that, when isolating to the single (high-cardinality) string-categorical variable, accuracies listed in decreasing order were:

TF-IDFnormalized, and thenTarget-EncodedTF-IDF Kmeansclassified, and thenTarget-EncodedTarget-EncodedOne-Hot Encoded

Actually, that is not a 100% accurate report since I did not include considering dropping the feature altogether. But I intentionally left this until stating everything above. It turns out, in the end, that the best option was to simply drop each high-cardinality string-categorical.

And here we are again… some of you are probably thinking: “DUH! I would have done that from the beginning!”

Believe me, that was my instinct. I wanted to do it. But, if you’re stubborn like me, you’ll want to back up your intuition and instinct with empirical evidence!

Which brings me to my next point…

Back to the Drawing Board

In my original notebook - yes, this was all condensed into one, giant, messy notebook originally - I started losing track of ALL the volumous amount of information I was tracking. And with each new experiment I would have to comment things out, write new code, and keep track of what was working and what wasn’t. I was getting tired of having this huge blob of spaghetti code.

Thus, I realized I needed to follow something like OSEMN not only in spirit but in execution! I needed to shift my thinking and do lots of refactoring but I knew that in the end it would make much more sense, be easier to run, and produce coherent output.

The Bottom Line: Workflow becomes Tangible (Execution)

I needed a workflow/process that would allow me to QUICKLY make changes to applicable preprocessing and transformation options and then see the results:

- in an agile manner that would not require me to either rewrite a notebook (comment out existing code and write new code)

- not require me to re-run EDA code preceding it when I only wanted to try a different combination of preprocessing/options

- be able to run modeling and hyper-parameter tuning separately from either EDA or preprocessing

In order to accomplish that, I realized this workflow/process must be data-driven, by some sort of configuration file. In this configuration file, the process would theoretically find a set of preprocessing options to apply to each feature in the data set. In theory, it should be a matter of simply changing preprocessing options in the config file, re-running the preprocessing routine, and then finally running the model-building routine if and when I wanted to see the result of that chosen set of options.

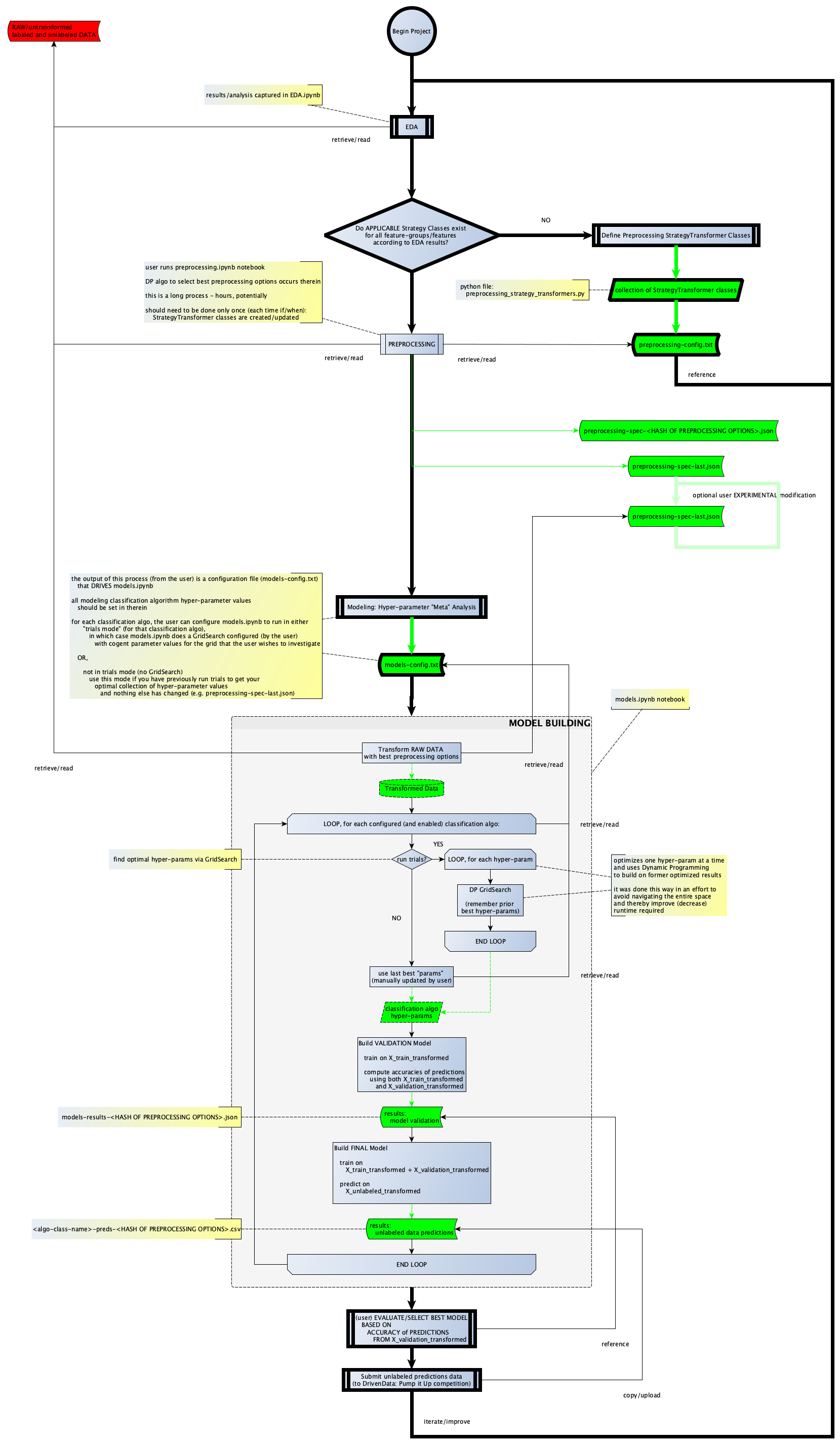

Skipping ahead a bit… after a few development cycles (and revisiting my EDA notebook), I had the data-driven workflow I wanted, to which I will provide a visualization shortly.

But once that was working, since I was driven to empirically optimize model creation, I realized that empirically optimzing model creation depends on empirically optimizing selection of the “best” preprocessing-options, now adaptable by virtue of my config file.

I moved on to the next phase.

Dynamic Programming for Best Preprocessing Options Selection

So far, this shift in thinking is all predicated upon definining ALL applicable preprocessing transformations that I might be interested in applying to a given feature, which should be the result of a COMPLETE and thorough EDA… and then translating each preprocessing option into a literal Python class that could be cited/referenced within the config file.

Building on my now-functioning idea of data-driven preprocessing steps, I figured if I adapted the format to include ALL possible and applicable preprocessing options in the config, I could write a Dynamic Programming algorithm that would feature-by-feature optimize the “best” preprocessing option simply by considering which one results in the best CUMULATIVE validation-accuracy.

Here’s a snippet from my actual preprocessing-config.txt file that drives the opimization algorithm contained my preprocessing.ipynb notebook:

"pump_age_at_observation_date__group": {

"description": {

"type": "engineered",

"description": "'The date the row was entered' - 'Year the waterpoint was constructed'"

},

"features": ["date_recorded", "construction_year"],

"preprocessing_options": {

// pump_age is a NEW/engineered feature, so there is only one option (which is done in required preprocessing) (we can NOT create it, which would mean leaving date_recorded and construction_year as is):

"pump_age": [

[

["date_recorded", "C__drop_it__StrategyTransformer"],

["construction_year", "C__drop_it__StrategyTransformer"]

],

[

["date_recorded", "C__drop_it__StrategyTransformer"],

["construction_year", "C__leave_it_as_is__StrategyTransformer"] // construction_year starts as an int so we CAN use it as is

],

[ // the idea here is to only use construction_year but with results from EDA applied to it

["date_recorded", "C__required_proprocessing__date_recorded__StrategyTransformer"], // this should probably be part of C__required_proprocessing__construction_year__StrategyTransformer as it is required for C__required_proprocessing__construction_year__StrategyTransformer

["construction_year", "C__required_proprocessing__construction_year__StrategyTransformer"], // construction_year starts as an int, this converts it to datetime type and replaces some weird values

["construction_year", "C__convert_to_int__construction_year__StrategyTransformer"],

["date_recorded", "C__drop_it__StrategyTransformer"] // need to do this after required preprocessing for construction_year since it uses date_recorded

],

//treat construction_year as categorical

[

["date_recorded", "C__drop_it__StrategyTransformer"],

["construction_year", "C__target_encode__not_LOO__post_encode_null_to_global_mean__StrategyTransformer"]

],

//treat construction_year as continuous

[

["date_recorded", "C__drop_it__StrategyTransformer"],

["construction_year", "C__replace_outliers_with_mean__StrategyTransformer"]

],

[

["date_recorded", "C__drop_it__StrategyTransformer"],

["construction_year", "C__replace_outliers_with_median__StrategyTransformer"]

],

[

["date_recorded", "C__drop_it__StrategyTransformer"],

["construction_year", "C__replace_0_with_nan__StrategyTransformer"]

],

//OTHERWISE... actually create the new pump_age feature

[

["pump_age", "C__required_proprocessing__pump_age__StrategyTransformer"]

]

]

}

}

In the above example, some of the preprocessing StrategyTransformer classes referenced are:

C__drop_it__StrategyTransformerC__leave_it_as_is__StrategyTransformerC__target_encode__not_LOO__post_encode_null_to_global_mean__StrategyTransformer

The complete list (and code) of each class can be found here.

Building a Baseline Model

One thing I need to mention is that the optimization algorithm depends on building as powerful and at the same time the most “basic” model as possible. What do I mean by this?

Well, we know for sure that, since the algorithm is trying to select the best preprocessing option from the list of those available (for a given feature), we want to build the “best” model we can - that is - one with the most features from the ORIGINAL/untransformed data set. From the EDA phase/notebook, we see that a lot of features contain null/missing values. Additionally, there are many string-categorical features.

Since this is a (multi-class) classification problem, for model building, algorithms such as DecisionTreeClassifier, RandomForestClassifier, XGBClassifier, etc. are considered. So it was decided to baseline using the most flexible classification algorithm (that can handle null/missing values) from those used in models.ipynb.

In theory, provided that a thorough EDA phase results in my producing applicable and well-defined StrategyTransformer classes, the algorithm contained within the preprocessing.ipynb notebook should find the based set of features and corresponding preprocessing options/transformations that will produced the model with the highest validation accuracy, all things being equal - e.g. excluding hyper-parameter tuning and ensembling (such as combining independent classification algorithms in a VotingClassifier), but these techniques have nothing to do with feature-selection and/or preprocessing options.

I have one final note prior to displaying the visualization of my formalized workflow: actual data preprocessing (from the selection of best preprocessing options occurring within preprocessing.ipynb) does not occur until the final phase, which occurs in models.ipynb.

Final (Formalized) Workflow

Modeling

There is not much to mention here, other than to point out the following:

- The end goal is to produce an array of models built from appropriate classification algorithms geared for multi-classification.

- The following classifications are used in the models.ipynb notebook:

DecisionTreeClassifierRandomForestClassifierXGBClassifierCatboostClassifier- Support Vector Machine (

SVM.SVC) - Ensembling:

BaggingClassifierVotingClassifier- specifically, the model which produced my highest leaderboard accuracy (so far) is this, using base estimators:RandomForestClassifierCatboostClassifierSVM.SVC

- The selection algorithm is based on

GridSearchCVat each hyper-parameter level.

Conclusion

In theory, holding everything else fixed - i.e. assuming the best preprocessing options have been selected - higher accuracies on unlabeled predictors may be achieved through more advanced ensembling techniques - e.g. stacking - which I have yet to explore and will likely be my next step.

I learned a TON while working on this project and I KNOW I am barely scratching the surface, here.

Have I mentioned how much fun I had?

Thank you for your time.

References

Pump it Up: Data Mining the Water Table. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.drivendata.org/competitions/7/pump-it-up-data-mining-the-water-table/

Mason, H. (2010). dataists » osemn. Retrieved from http://www.dataists.com/tag/osemn/

Prokopev, V. (2018). Mean (likelihood) encodings: a comprehensive study. Retrieved from https://www.kaggle.com/vprokopev/mean-likelihood-encodings-a-comprehensive-study

Cerda, P., & Varoquaux, G. (2020). Encoding high-cardinality string categorical variables [Ebook]. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1907.01860.pdf